October 2023

Caesura Presents…Abigail Chabitnoy

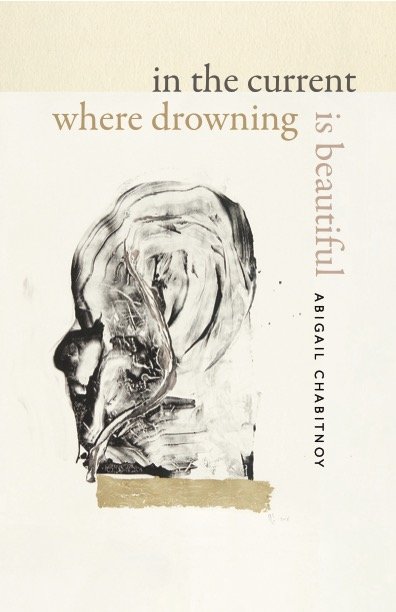

Abigail Chabitnoy is the author of In the Current Where Drowning Is Beautiful (Wesleyan 2022); How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan 2019), shortlisted for the 2020 International Griffin Prize for Poetry and winner of the 2020 Colorado Book Award; and the linocut illustrated chapbook Converging Lines of Light (Flower Press 2021). Her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Boston Review, Tin House, Gulf Coast, LitHub, and Red Ink, among others. She currently teaches at the Institute of American Indian Arts low-residency MFA program and is an assistant professor at UMass Amherst. Abigail is a member of the Tangirnaq Native Village in Kodiak.

Website: https://salmonfisherpoet.com

Order at:

https://www.weslpress.org/9780819500120/in-the-current-where-drowning-is-beautiful/

Wesleyan University Press, November 2022

$15.95 / 104 pages

Poetry as Survival Technique

John:

Congratulations on the publication of In the Current Where Drowning is Beautiful! In it, I see many similarities to your previous collection, How to Dress a Fish, in how you explore deeply personal cultural themes and relate them to contemporary and historical struggles, including violence against women, Indigenous peoples, and nature. However,Current lays these inherent connections even more bare while also expanding them. Can you speak to how Current acts as both a natural complement and natural progression from your earlier work?

Abigail:

Thanks so much John. Yes, in many ways I’m still trying and failing to write a certain particular work that planted itself in my brain many years ago in a single image that is only slowly revealing its significance to me as patterns and lines repeat and accrue. How to Dress a Fish began from a desire to engage with the language and motifs of myth and the supernatural but in so doing became entangled, enamored, with history. That work, of course, raised as many new questions as it might have answered, and beyond the physical stacks of pages I still have left over from that project, chief among the questions that remained was one put forth in a workshop: where were the women?

I’ve spent a great deal of time lately questioning what the poem does or can or should do, why it is I insist on inviting such agitation into my daily practice. But the truth is, I engage with the world through writing. I attempt to locate myself through writing, but more than myself, I attempt to locate myself in proximity to those I am responsible to. That idea of responsibility really gained traction in How to Dress a Fish, and In the Current Where Drowning Is Beautiful I felt compelled to look forward, toward some kind of hope that was genuine and rigorous enough to withstand the unceasing onslaught of dismal news, the large and small fears and anxieties that dictate my existence, real, imagined, imminent or unlikely as they might be in a given moment. It's funny to me now, as a mother to a ten-month-old girl, to read these poems, many of which it’s clear I imagined writing to a daughter at a time in my life when I was convinced I would not have children. And of course, she is already sending ripples through my newer work, which continues to interrogate my own culpability—and responsibility—to past and future.

John:

What an interesting situation. I too have a collection in which I wrote poems to my children, though at the time I didn’t have any. Now I have twin six-year-olds. How has becoming a parent changed your perspective and creative process? How has it enhanced your connection to the past and present, to your heritage? And I’d love to know more about what you mean by “my own culpability.”

Abigail:

Goodness—I thought I wanted twins. One is more than a handful! It hasn’t quite had the impact on my image landscape I was hoping yet, but that’s possibly because I deliberately gave her a water-heavy name. It has absolutely changed my process in some ways, while also affirming previous tendencies. I’ve always been a note taker. I was scolded in a middle-school German class by my teacher for trying to take notes. “Why are you always writing?” she asked. But I couldn’t comprehend how to process learning, how to really take in new information other than passively without writing. I am trying to get better at letting ideas percolate, but I’ve also had to embrace writing in notes and fragments simply for the practical matter of my time constraints. I accepted a position as assistant professor at UMass Amherst the same week my daughter was born and we have not yet been able to find daycare, which has certainly been a mixed blessing. I get to spend invaluable time with my daughter when she’s most dependent on me; I get a reminder to relax and take in her experience of the world; but through writing, I’m also able to as I need use writing to dive more fully in the experience of the moment, or remind myself that I also exist outside of this current, sometimes overwhelming and consuming role of “mother.”

But if anything, it’s continued to trouble my connection to my past and heritage. Despite family claims of strong “Chabitnoy” genes, my girl came out looking just like her daddy. Blonde hair, blue eyes, milky skin. By blood, of course, further removed. And my new position required us to move from the Pacific Northwest where I’d ironically finally moved specifically to be able to raise my daughter closer to indigenous networks of women. I’ve also had far less time to keep up with my language studies, though after this grace year, I plan to reevaluate my pursuits and make language more of an integral part of our daily lives. This troubling has also, I think, led me to reflect on my culpability—that is, while I write about patterns and narratives that facilitate violence, and write about the consequences of climate collapse, I can’t simply deny my own settler-colonial, imperial US, capitalist/consumer inheritance, habits, and behaviors. How do I reckon with these consequences and uncomfortable questions on and off the page, and how to I write to a future I grow increasingly wary for while investing absolutely in that future if for no other sake than my own selfish mother-love?

John:

What a compelling story! With biracial children myself (me being the Caucasian/imperial side), I’ve also struggled how best to explore and articulate it in my poetry. I’m looking forward to seeing how this dynamic plays out in your new poetry.

Speaking of cultural dynamics, now that indigenous peoples have the chance to tell their own stories, unfiltered by the imperial perspective, do you feel a sense of responsibility to set history straight? How does one go about rewriting a disingenuous legacy?

Abigail:

That sense of responsibility is a tricky beast, in relation to any number of possible endeavors. Is this a responsibility all writers from previously misrepresented or silenced demographics have? Is it specific to Indigenous writers because of the idea of communal responsibility as opposed to individual rights? Is that a fair mantle to overlay on every indigenous writer? Then of course we slip into what is it to write “Indigenous Literature” (the subject of my spring semester, for completely selfish reasons). These are indeed the questions that keep me up at night and make me think perhaps I should have focused more on soccer or even followed through on my post-grad school threats to go to culinary school and become a baker instead!

I will say that when I am working with material that is in any way tied to my Indigenous heritage, I feel a sense of responsibility to carefully consider how I am presenting that material. And while my first book was heavily interested in history, and I do still have more questions/interest/material to pursue in that direction, I am also a poet and not an historian. So, when my writing is called in that direction, I want to be responsible. But I also think it’s important to allow writers of such populations and communities to pursue interests and art of their choosing, rather than limit the scope of their visions. And that question of “disingenuous legacy” is also difficult to tackle in that I don’t think there’s a single way to go about it or a single legacy to replace a faulty one with. That’s kind of the point—these histories and stories are living and relational. They’re fluid, in flux. Not fixed as products but rather continually in process. It depends who is standing at the center of the text. Shifting that center sounds to me like a good place to start—but there are any number of ways of affecting such a shift. My primary concern is the quality of the poems, as determined by my personal aesthetics and the demands I place on myself. I do think poetry can achieve these goals and I don’t think it’s possible to separate poetry from politics. To suggest as much belies a privileged and frankly narrow-sighted vantage point. But if policy change or historical revision are my primary goals, there are more effective mediums and genres than poetry, in my opinion.

I also, last thought, think it’s important to recognize Indigenous peoples have been telling their own stories, in their own ways, according to their own agendas. What is emerging are more prevalent platforms and greater visibility—which is important to continue to facilitate and build. And our readers continue to represent a variety of experiences themselves which affects how their perspective and reading of the work is filtered.

John:

When discussing culturally significant themes that you have such strong feelings on, how do you express your worldview subtly, avoiding didacticism? How do you make a point without preaching?

Abigail:

Oh John, every time I cringe at how much time I’ve let slide between answering your delightfully thoughtful questions, I realize it’s been precisely the time that was needed. I will admit, this was actually my first poetry mentor’s greatest concern and challenge she first set for me! As it happens, I was having a conversation this morning with Saretta Morgan, not directly about this, but indirectly perfectly in response to this. We were discussing the progression of drafts, specifically, from what we begin writing and thinking we need to write—what we think we have/need to say, in somewhat plain language, perhaps, or in a manner direct, raw, immediate. But as we continue to work, as we continue to knead the language, and sit with our language and the experience we were initially attempting to capture, our own experience and understanding of our needs and our words (should) evolve. That is the alchemy of poetry. That act of transformation. We find the language we need not to communicate information, but to arrive at what we need—and that need must be defined by the individual writer. But, for the reader, what we finally deliver on the page should be an invitation into an experience of coming to know. An experience of knowing.

Coincidentally, I’ve been reading Indigenizing Philosophy through the Land and, despite the disservice of the press’s unpardonable lack of proofreading, this work too seems to be speaking to this offering of the poem to writer and reader. In Western thought, knowledge is something static, unchanging, dependent on fixed proclamations that make claims of universality and consistency even as they neglect any engagement with context and with the experience of the individual. In non-Western systems of knowing, however, knowing is a verb. It is something to be experienced. The “recipient” of knowing is rather a participant, a creator in the act of making/knowing. It requires presence and locality and genuine engagement.

To attempt to provide an answer that might actually be helpful to put in practice, I’m personally very fond of playing with the elasticity of language. In my teasing of the “bon mot”, I allow myself to be delighted by errors in transcription or line breaks or homonyms that introduce other associations or thought trails or images or ideas that I didn’t intend or plan. I allow the poem to become a site of discovery and multiplicity. I let the language—and myself—play. This is how I escape the trap of intent. Otherwise, why shouldn’t I be writing a sermon, op-ed, news article, or any other medium designed to communicate facts and information?

I think, operating in this way, the “point” emerges naturally through a recognition and embrace of my obsessions. I can’t make it through a reading without saying the word “teeth” at least a dozen times. It’d make a fun drinking game, to be honest. And while I hope each use is different or lands differently in some way, the concerns I am most invested in while writing (which feels a truer word than “point”) echoes through the pages.

John:

Thank you so much for such beautiful honesty and vulnerability. I cannot express how much “recognition and embrace of my obsessions” means to me. How does poetry affect and effect you emotionally? Does it help pull you out from some inner darkness? Or, the reverse, does it allow you to explore that inner darkness in a safe environment, perhaps with a sense of catharsis? Or perhaps both simultaneously?

Abigail:

Thank you for providing such provocative questions and allowing me the space and impetus to sit with my thoughts! I feel as though everything has been happening so quickly lately in my life that I’m forever reading what other people have to say on the matter and rarely taking a breath to check in on my own thoughts! Truthfully, I think poetry provides as much for me outside of the “poem proper” in terms of the community and conversation it has fostered in my life. But as for the page itself, I suppose part of the answer might be simply company in times of unrest a la the original (darker) Grimm fairy tales. I’m not sure if I’d use the word cathartic, but I can’t think why not. Truth be told, I suspect in life I’m actually a coward. I have personally been fortunate enough to not have experienced much significant trauma, but I am daily overcome by fear. I do suffer greatly from anxiety and have for as long as I can remember. Despite how I might carry myself, or my career through college in sports, my crisis of confidence is not by any means a play for praise. I’m not sure where this sense of not being enough is rooted (though being raised in a faith that takes as its basic premise that we are all born in a state of inherent flaw and wickedness surely didn’t help), but I have an overdeveloped drive that manifests most regularly in an irritable restlessness. Besides keeping my company in my fear, poetry provides an outlet for that restless energy; a sense of participating in something beyond myself and I suppose tricking myself into relinquishing the burden to have answers. John, you seem to have struck a nerve! (Kidding, of course.) I will say, however, that as chaotic as my life has been since moving and taking up a new job and learning to be a mother, I have begun to recognize I am noticeably more irritable and restless and short with others when I have not been able to spend time with my own creative work and am learning to simultaneously grant myself more grace in meeting the terms of my overdeveloped sense of ambition while still protecting fiercely the needs of my writing practice, even if imperfectly.

John:

I absolutely understand. I’ve found similar changes in myself since becoming a parent.

For my final question, let’s lighten things up a bit.

Apart from creativity, what fills your life with joy, with meaning? And can you say one thing about yourself that might surprise us?

Abigail:

Apart from creativity, and in fact in a space I actively resist any feeling of a sense of responsibility to be inspired poetically, I find the most joy outdoors. Walking my dogs, going on hikes, getting into the mountains, or out on the water.

As for something surprising. Hmm. I suppose you might be surprised that through college, I had no interest or ambition to be a poet. In fact, poets intimidated me. I wanted to write fantasy, to be honest, and when I was told upon acceptance into my first fiction workshop that “we don’t do that here” I reoriented myself to writers like Borges and Italo Calvino. I very nearly went to CalArts where I intended to find artists to collaborate on stop-motion pieces such as Tim Burton and Neil Gaiman had created. I’d like to rediscover the sense of play and wide-eyed possibility I held then, but I am forever grateful for my mentor Michelle Gil-Montero who showed me I could in fact also be a poet (and convincing me that my fiction, lacking in plot, dialogue, or any recognizable character development) was in fact prose poetry.